Henry Ossawa Tanner # 1497

$ 8.00

Caption from poster__

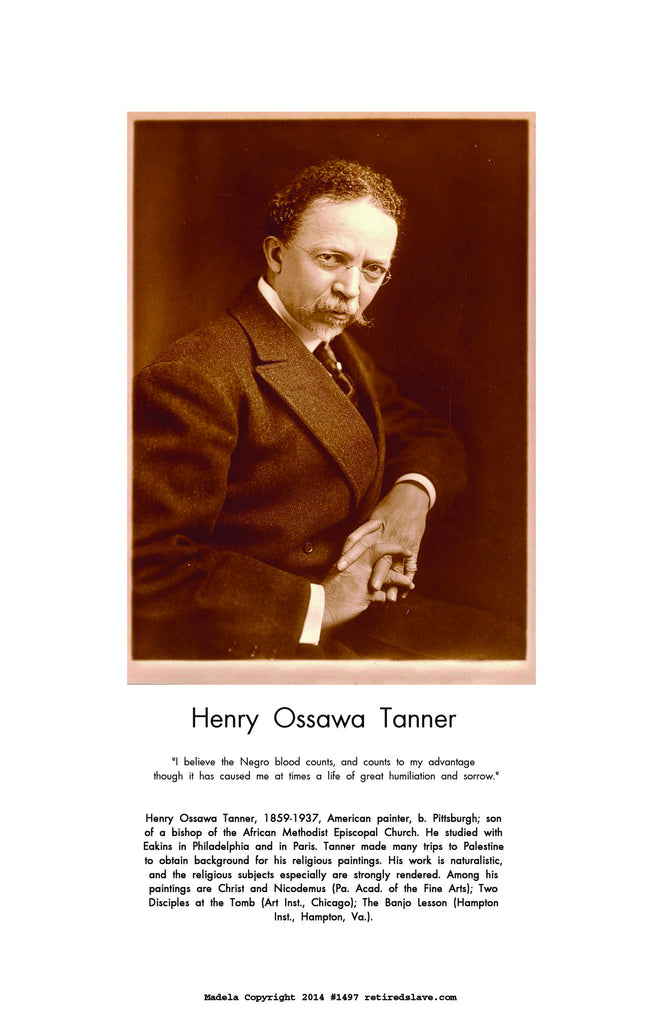

Henry Ossawa Tanner

“ I believe the Negro blood counts, and counts to

my advantage though it has caused me at times

a life of great humiliation and sorrow.”

Henry Ossawa Tanner, 1859-1937, American painter, b. Pittsburgh; son of

a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He studied with Eakins

in Philadelphia and in Paris. Tanner made many trips to Palestine to obtain

background for his religious paintings. His work is naturalistic, and the

religious subjects especially are strongly rendered. Among his paintings are

Christ and Nicodemus (Pa. Acad. of the Fine Arts); Two Disciples at the

Tomb (Art Inst., Chicago); The Banjo Lesson (Hampton Inst., Hampton,

Va.). The son of a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church,

Henry Ossawa Tanner was raised in an affluent, well educated African

American family. Although reluctant at first, Tanner's parents eventually

responded to their son's unflagging desire to pursue an artistic career and

encouraged his ambitions. In 1879, Tanner enrolled at the Pennsylvania

Academy of Fine Arts, wherehe joined Thomas Eakins's coterie. Tanner

moved to Atlanta in 1889 in an unsuccessful attempt to support himself

as an artist and instructor among prosperous middle class African

Americans.Bishop and Mrs. Joseph C. Hartzell arranged for Tanner's first

solo exhibition, the proceeds from which enabled the struggling artist to move

to Paris in 1891. Illness brought him back to the United States in 1893, and

it was at this point in his career that Tanner turned his attention to genre

subjects of his own race. In 1893 most American artists painted African

American subjects either as grotesque caricatures or sentimental figures

of rural poverty. Henry Ossawa Tanner, who sought to represent black

subjects with dignity, wrote: "Many of the artists who have represented

Negro life have seen only the comic, the ludicrous side of it, and have

lacked sympathy with and appreciation for the warm big heart that dwells

within such a rough exterior ." The banjo had become a symbol of derision,

and caricatures of insipid, smiling African Americans strumming the

instrument were a cliche. In The Banjo Lesson, Tanner tackles this stereo-

type head on, portraying a man teaching his young protege to play the

instrument the large body of the older man lovingly envelops the boy as

he patiently instructs him. If popular nineteenth-century imagery of the

African American male had divested him of authority and leadership,

then Tanner in The Banjo Lesson recreated him in the role of father,

mentor, and sage. The Banjo Lesson is about sharing knowledge and

passing on wisdom. The exposition-sized canvas was accepted into

the Paris Salon of 1894. That year it was given by Robert Ogden of

Philadelphia to Hampton Institute near Norfolk, Virginia, one of the

first and most prestigious black colleges founded shortly after

Emancipation. Hampton lent it the next year to Atlanta's Cotton

States and International Exposition of 1895, where it hung in the

Negro Building. Contemporary critics largely ignored the work.

Tanner painted another African American genre subject in 1894,

The Thankful Poor, but then abandoned subjects of his own race

in favor of biblical themes. When Tanner returned to Paris in 1895,

he established a reputation as a salon artist and religious painter

but never again painted genre subjects of African Americans.