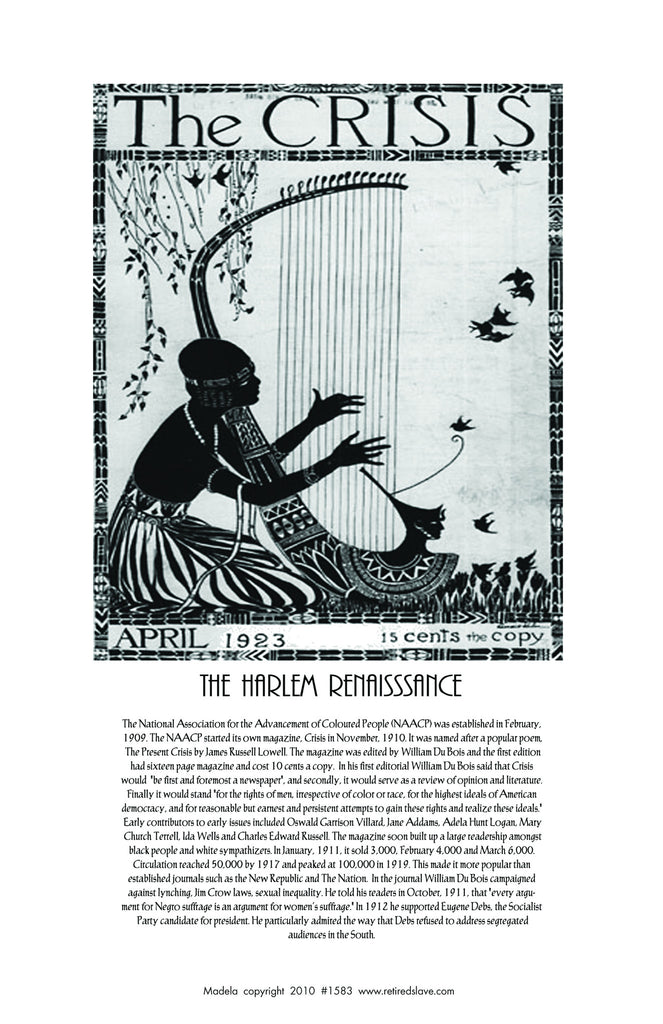

Harlem Renaissance #1383

$ 8.00

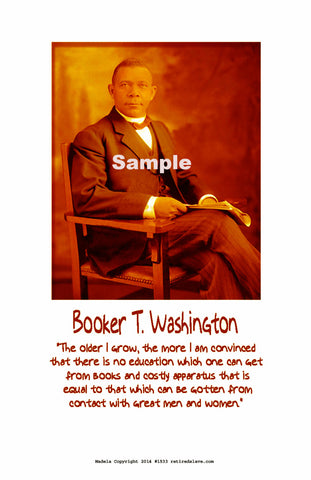

Caption from poster__

Harlem Renaissance

The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People

(NAACP) was established in February, 1909. The NAACP started

its own magazine, Crisis in November, 1910. It was named after a

popular poem, The Present Crisis by James Russell Lowell. The

magazine was edited by William Du Bois and the first edition had

sixteen page magazine and cost 10 cents a copy. In his first

editorial William Du Bois said that Crisis would "be first and fore-

most a newspaper", and secondly, it would serve as a review of

opinion and literature. Finally it would stand "for the rights of men,

irrespective of color or race, for the highest ideals of American

democracy, and for reasonable but earnest and persistent attempts

to gain these rights and realize these ideals." Early contributors to

early issues included Oswald Garrison Villard, Jane Addams, Adela

Hunt Logan, Mary Church Terrell, Ida Wells and Charles Edward

Russell. The magazine soon built up a large readership amongst

black people and white sympathizers. In January, 1911, it sold

3,000, February 4,000 and March 6,000. Circulation reached

50,000 by 1917 and peaked at 100,000 in 1919. This made it

more popular than established journals such as the New Republic

and The Nation. In the journal William Du Bois campaigned

against lynching, Jim Crow laws, sexual inequality. He told his

readers in October, 1911, that "every argument for Negro suffrage

is an argument for women's suffrage." In 1912 he supported

Eugene Debs, the Socialist Party candidate for president. He

particularly admired the way that Debs refused to address

segregated audiences in the South.

Harlem Renaissance 1920 -1940 Originally called the New Negro Movement. The Harlem Renaissance was a literary and intellectual flowering that fostered a new black cultural identity in the 1930s, and 1930s. Critic and teacher Alain Locke described it as a "spiritual coming of age" in which the black community was able to seize upon its "first chances for group expression and self determination." With racism still rampant and economic opportunities scarce, creative expression was one of the few avenues available to African Americans in the early twentieth century. Chiefly literary the birth of jazz is generally considered a separate movement the Harlem Renaissance, according to Locke, transformed "social disillusionment to race pride. The timing of this coming of age was perfect. The years between World War I and the Great Depression were boom times for the United States, and jobs were plentiful in cities, especially in the North. Between 1920, and 1930, almost 750,000 African Americans left the South, and many of them migrated to urban areas in the North to take advantage of the prosperity and the more racially tolerant environment. The Harlem section of Manhattan, which covers just 3 sq mi, drew nearly 175,000 African Americans, turning the neighborhood into the largest concentration of black people in the world. Black-owned magazines and newspapers flourished, freeing African Americans from the constricting influences of mainstream white society. Charles S. Johnson's Opportunity magazine became the leading voice of black culture, and W.E.B. DuBois's journal, The Crisis, with Jessie Redmon Fauset as its literary editor, launched the literary careers of such writers as Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, and Countee Cullen. Other luminaries of the period included writers Zora Neale Hurston, Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Rudolf Fisher, Wallace Thurman, and Nella Larsen. The movement was in part given definition by two anthologies: James Weldon Johnson's The Book of American Negro Poetry and Alain Locke's The New Negro. Our Individual Dark-Skinned Selves" The white literary establishment soon became fascinated with the writers of the Harlem Renaissance and began publishing them in larger numbers. But for the writers themselves, acceptance by the white world was less important, as Langston Hughes put it, than the "expression of our individual dark skinned selves.