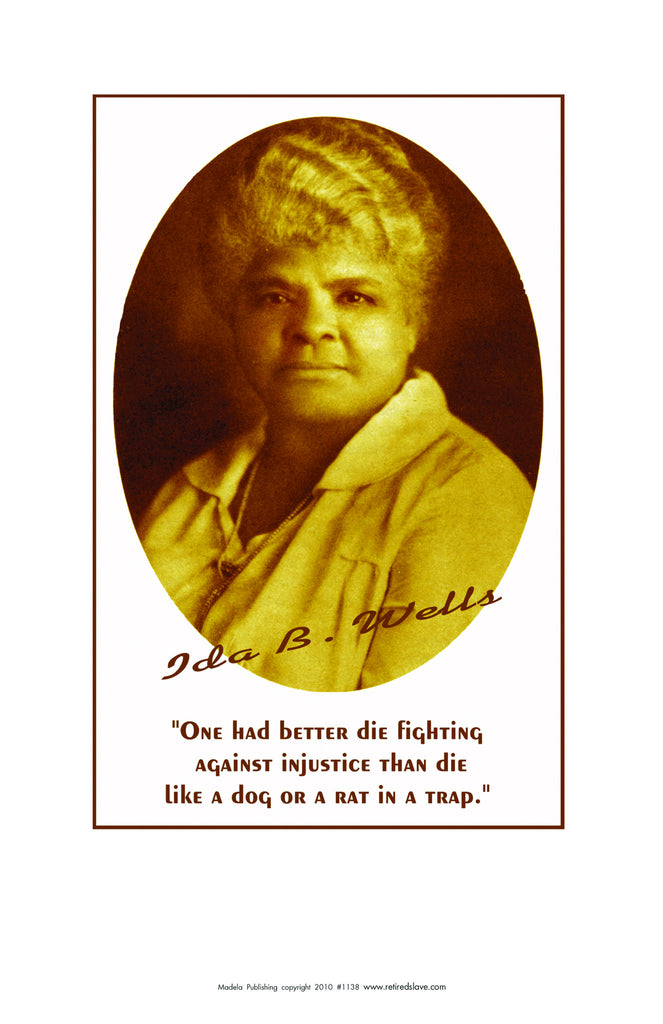

Ida B. Wells #1138

$ 8.00

Caption from poster__

“ One had better die fighting

against injustice than die

like a dog, or a rat in a trap.”

Ida B. Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her father (James Wells) was a carpenter and her mother ( Elizabeth"Lizzie Bell" Warrenton Wells ) was a professional cook. Her parents were slaves but the family achieved freedom in 1865. When Wells was 16 both her parents and an older brother died of yellow fever during an epidemic that swept the South. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided that the five remaining Wells children should be farmed out to various aunts and uncles. Wells was devastated by the idea and to keep the family together, dropped out of high school, and found employment as a teacher in a local black school. In 1880, Wells moved to Memphis, where she continued teaching. During the summer sessions, she attended Fisk University in Nashville. Wells held strong political opinions and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24, she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge." Wells became a public figure in Memphis when in 1884 she led a campaign against segregation on the local railway. In 1884, she was asked by the conductor of the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company to give up her seat on the train to a white man and ordered into the smoking or "Jim Crow" car, which was already crowded with other passengers. The federal Civil Rights Act of 1875 banning discrimination on the basis of race, creed or color, in theaters, hotels, transport and other public accommodations, had just been declared unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases (1883). So, several railroad companies defied this congressional mandate of the 1875 Act and racially segregated their passengers. Wells refused to give up her seat, 71 years before Rosa Parks, and the conductor, who was assisted by two other men, dragged her out of the car. When she returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the railroad. She won her case in the local circuit court, but the railroad company appealed to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which reversed the lower court's ruling, in 1887. During her participation in women's suffrage parades, her refusal to stand in the back because she was black resulted in the beginning of her media publicity. In 1889, she became co-owner and editor of an anti-segregationist newspaper based in Beale Street in Memphis. In 1892, however, she was forced to leave Memphis because her editorials in the paper, Free Speech, were seen as too agitating. 1892 was the same year that she published her famous pamphlet, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. In 1895, she published A Red Record, which documented her campaign against lynching. In 1895, in Chicago, she married attorney Ferdinand Lee Barnett, who founded and edited the Chicago Conservator, the city's first black newspaper. The couple had four children.Their children were Charles, Ferdinand, Ida, and Alfreda. Although Wells tried to retire from public life to raise her children, she soon returned to her campaign for equal rights. In 1906, she joined with W.E.B. Du Bois to promote the Niagara Movement, a group which advocated full civil rights for Blacks. In 1910, Wells helped form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (the NAACP). She never obtained a position of leadership within the NAACP, perhaps because she opposed Booker T. Washington's moderate position that blacks focus on economic gains rather than social and political equality with whites. Or perhaps it was because at this time women did not have such power. She founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the first black suffrage organization in 1913, and from l913-16 worked as a probation officer in Chicago. The poet Langston Hughes said her activities in the field of social work laid the groundwork for the Urban League. In 1930, she ran for the Illinois state legislature, one of the first black women ever to run for public office. She died in Chicago, Illinois, where a public housing complex was later named in her honor. There is also a high school named after her, on Hayes Street in San Francisco, California. After her retirement, Wells wrote her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928). She died of uremia on March 25, 1931. Throughout her life, Wells was militant in her demands for equality and justice for African-Americans, and insisted that the African-American community must win justice through its own efforts.